As high as the stakes are in modern Formula 1, the battle for the sport’s future which raged at the dawn of the eighties was fought with particular ferocity. The political fall-out even led to some races being cancelled.

But, as a trove of documents unearthed by @DieterRencken reveals, this fraught period in the sport’s history played a unique role in shaping modern F1.In early 1980 Formula 1 was a battleground. The lines were drawn between the mostly British teams, dubbed ‘garagistes’ by Enzo Ferrari on account of building cars using proprietary components from suppliers (Cosworth engines, Hewland gearboxes), and their opponents headed by FISA, then the sporting arm of the FIA. The FISA-aligned teams ‘grande’ teams included manufacturers Ferrari, Renault and Alfa Romeo, who surveyed the ongoing skirmishes nervously, and periodically switched allegiances according to their agendas.

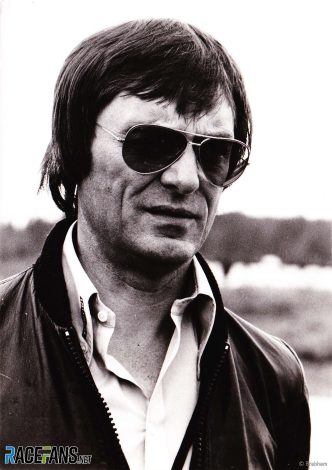

The ‘garagistes’ battled under the aegis of the Formula One Constructors Association (FOCA). This was chaired (but not, contrary to lore, founded) by Bernie Ecclestone, who also ran championship front-running team Brabham. His right-hand man at FOCA was former barrister and March co-founder Max Mosley. Their nemesis was FISA president Jean-Marie Balestre, who transformed the FIA’s International Sporting Commission into FISA in 1978 (and was, by most accounts, rather belligerent.)

Their battle was fought so fiercely because the issue at stake was nothing less the ownership of F1’s commercial rights.

Balestre attempted to claim financial control behalf of both F1 championships, then known as the World Championship for F1 Drivers and International Cup for F1 Constructors, on behalf of FISA. FOCA had negotiated deals with promoters on behalf of the sport’s teams and divided the spoils according to a pre-agreed structure. This was what Balestre had in his sights.

Battles were also fought over F1’s rules. In addition, Balestre was adamant FISA could make immediate regulatory changes if they were considered critical for safety, while FOCA demanded at least two years’ notice for changes, unless a shorter period was mutually agreed.

The scene was set for the ‘FIASCO war’, as the conflict came to be known. US journalist Forrest Bond, a long-standing friend of mine, is believed to have coined the phrase after juggling various initials to describe a conflict that was publicly waged on various fronts.

The first major casualty was the 1980 Spanish Grand Prix, which was retrospectively stripped of its championship status after Balestre withdrew FISA’s sanction. Even Hollywood scriptwriters would have experienced difficulties in fabricating the backstory.

During the previous race in Monaco, Balestre decreed that all drivers should attend a 45-minute briefing despite it not being enshrined in the regulations. The drivers, under orders from their FOCA-linked teams, stayed away. FISA responded by handing down $2,000 fines to each of them, which they refused to pay under orders from their bosses.

The stakes were raised even higher when FISA suspended the drivers’ licences. This was despite the race promoter offering to pay the fines, an offer Balestre refused to accept unless it was accompanied by proof of payment from the drivers, therefore constituting admission of guilt.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Nonetheless the race went ahead on the insistence of King Juan Carlos of Spain in his joint capacity as monarch and royal patron of organising club Real Automóvil Club de España. FISA’s reaction was to strip the grand prix of its championship status.

Just when meltdown seemed certain, a modicum of sanity broke out: after a 13-hour negotiation session in Paris, on 19 January 1981 the factions announced a peace deal had been agreed. Known as the Concorde Agreement – the first of six such documents, the last of which expired in 2012 (before being replaced by the current bilateral agreements) – the covenant was signed in the FIA/FISA offices on place de la Concorde – hence the name, which translates as “agreement” in English.

Common sense did not, though, immediately prevail: No sooner had Concorde been signed than FISA insisted the date for 1981 season opener, the South African Grand Prix scheduled for February 7th at Kyalami, must change. Ecclestone, who had acquired the cash-strapped circuit but sold it in 1980 to what was believed to be a front company, was incandescent with rage, particularly as FOCA had underwritten the race.

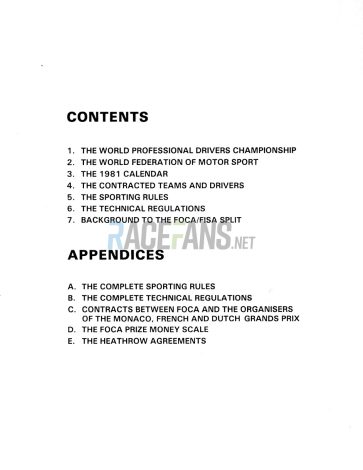

Time, then, to wheel out the breakaway series, to be known as the World Professional Drivers Championship, sanctioned by the equally new World Federation of Motor Sport. Unlike the later series threatened by FOCA’s noughties equivalent FOTA, which quickly floundered on undeliverable hyperbole, the WPDC was able to trot out regulations and – crucially – a draft calendar based on race promoter contracts.

Tellingly, in his autobiography Mosley notes that FOCA “would probably not have been able to race in [Long Beach, the next championship round] for lack of money.” The outcome of the war truly had been poised on a knife-edge.

Strangely, there are few online references to WPDC or WFMS. Yet this championship arguably created the way forward for F1, creating as it did – for better or worse – the cornerstones of many of the sport’s revenue and governance structures, some of which exist to this day – the primary differentiator being that teams needed to be constructors.

During last year’s US Grand Prix I stayed with Forrest, who lives less than an hour’s drive south of Austin. The weekend coincidentally marked my 65th birthday, and he presented me with a priceless gift: a stack of original WFMS/WPDC documents. They make for fascinating reading, and explains just how and why F1 evolved the way it did.

For starters, the document rips into FISA, and Balestre. “As [he] is demonstrably incapable of running the sport, there is little reason to think that he would have done any better with the commerce”, it states. “FISA’s presence at a Grand Prix used to depend on the weather conditions and quality of the parties”, it adds, noting the governing body’s representation ranged “from 100 at Monaco to as few as one at less attractive venues.”

However, aside from snide remarks – which remind one of comments made by Mosley during his FIA presidency – the pack shines a light on the incredible thought, effort and foresight Ecclestone put into FOCA during its early days. That in turn enabled FOCA to grow into the Formula One Group, which was subsequently acquired by CVC Capital Partners before onward sale to current owners Liberty Media at an valuation of $8bn.

Although WPDC’s sporting and technical regulations were based very much on prevailing rules, there are some gems, such as the introduction, which states:

“There are only four parameters which control the performance of a racing car:

a) the engine power available

b) the aerodynamic download which can be generated

c) the area and effectiveness of tyre rubber in contact with the ground

d) the weight of the vehicle”

The regulations provide for stability by demanding that performance rules – as per the parameters outlined above – cannot be changed with less than “two clear years’ notice”; where major engine changes are introduced, there was to be a period of validity of four years after two clear years notice. Safety-driven changes, though, needed unanimity to waive the lead times – which points to rather cavalier attitudes towards lives and limbs…

The technical regulations stipulated that when a “[constructor] fits an engine it does not manufacture, the car shall be considered a hybrid”, “all vehicles must have a reverse gear which must be in working order”, and “a starter capable of starting the car must be carried aboard at all times”. The weight of car in running order was to be 575 kilograms.

The clause relating to fuel tanks illustrates just how much progress F1 has made in terms of fuel and thermal efficiency over the past 40-odd years. The WPDC regulations note “the total capacity of the fuel tanks shall not exceed 250 litres” – for 3-litre engines producing around 500bhp. Today’s 1000bhp, 1.5-litre hybrids require half that amount to cover the same race distance of “not less than 190 miles (304km) and not more than 200 miles (320km).”

Race promoter contracts contain equally quaint provisions: “The constructors will ensure that the drivers of any car finishing the race in first, second or third will (except in the case of force majeure) attend the victory ceremony, provided it is not longer than half an hour, is held at the circuit within half an hour of the finish of the race, and that its time and place were agreed in writing between the constructors and the promoters.”

“In the event that television coverage of the race exceeds the following number of audience/minutes worldwide of 500 million for [year],” it adds, “the constructors shall be entitled to 50 per cent of the total revenue for the year in which the race takes place arising from the sale by the promoters or any other party of trackside advertising of any kind at the circuit at which the race takes place.”

Go ad-free for just £1 per month

>> Find out more and sign up

Bear in mind that races then – as now – ran to around 100 minutes, so a full race broadcast was expected to attract five million viewers, or multiples thereof in the event of highlights packages. By way of comparison, last year’s Monaco Grand Prix TV audience peaked at 110m.

Equally illuminating are stipulations that promoters must provide the “constructors with an additional 250 passes providing free access to the circuit, paddock, garages, pit complex boxes and pit complex”, in addition to the passes the teams issue to their own staff.” Presumably Ecclestone was already eyeing sponsors and hospitality, for another clauses demands that an area of “not less than 200 metres by 160 metres adjoining the paddock for the promotional facilities of the teams’ sponsors.”

- 20% Qualifying

- 45% Race

- 35% Contractual compensations

The top 20 qualifiers shared the 20% pot on a sliding scale of 2% for pole position to 0.4% for 20th. Where races included up to 24 cars, those in the last two rows did not qualify for qualifying money.

The table for division of the race kitty was, though, more complex: the race fund was divided into four parts, with 64 per cent being paid on a sliding scale from 6.5% for victory to 0.3% for 20th place, and 36 per cent spilt three ways for placings at one-quarter, one-half and three-quarters race distance – using the same percentages splits.

The so-called “contractual compensation” kitty provides the basis for F1’s current revenue structure – albeit without today’s inequity of special bonuses paid to the major teams simply for turning up – and looks like a forebearer of the current column one and column two payments in that the 35% fund detailed above is spilt into two sums.

The first amount was split equally amongst between 20 eligible cars (saliently, not 10 teams), while the second amount arrived at by taking the amount “divided by the number of point accrued in the (note) previous two half seasons” – so the second half of 1980 was added to the first half of 1981, etc…

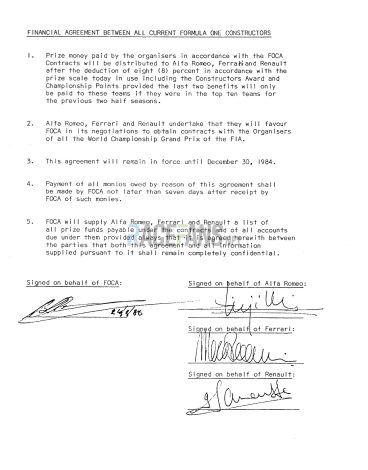

Equally amusing is a financial agreement between FOCA and Ferrari, Alfa Romeo and Renault, who were not members of the teams association at the time, which allowed FOCA to collect a commission on monies received on behalf of all teams.

As history relates, long-term peace eventually prevailed in F1 – the occasional skirmish aside – after all the teams fell in line with FOCA and the FIA, the latter absorbing FISA during Mosley’s presidency.

Thus FIASCO ultimately paved the way for the appointment of the Formula One Group as the sport’s commercial rights holder, albeit only after a controversial 113-year deal was entered into between Ecclestone and Mosley’s administration – a deal that, crucially, excluded the teams. That, though, is a story for another day…

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

RacingLines

- The year of sprints, ‘the show’ – and rising stock: A political review of the 2021 F1 season

- The problems of perception the FIA must address after the Abu Dhabi row

- Why the budget cap could be F1’s next battleground between Mercedes and Red Bull

- Todt defied expectations as president – now he plans to “disappear” from FIA

- Sir Frank Williams: A personal appreciation of a true racer

Garns (@)

23rd January 2019, 12:26

@dieterrencken

Love these old stories about F1 Dieter. I stared watching F1 in 1985 when it come to Adelaide but as a young kid you have no idea about the politics and power struggle if F1’s history. Many see the 80’s as F1 at its best (which will vary depending on viewers ages of course) but it was really in turmoil behind the scenes.

Phylyp (@phylyp)

23rd January 2019, 12:32

Ah, the perfect sort of reading for the gap between seasons!

Dave F. (@dave-f)

23rd January 2019, 13:09

A very interesting read.

To be a pedant, surely ‘concorde’ translate to English as concord?

Dieter Rencken (@dieterrencken)

23rd January 2019, 15:21

Concorde Definition

1a : a state of agreement : harmony. b : a simultaneous occurrence of two or more musical tones that produces an impression of agreeableness or resolution on a listener — compare discord. 2 : agreement by stipulation, compact, or covenant. 3 : grammatical agreement. Concord.

Glennb

24th January 2019, 3:17

Concorde is a British-French turbojet-powered supersonic passenger airliner that was operated from 1976 until 2003. It had a maximum speed over twice the speed of sound at Mach 2.04, with seating for 92 to 128 passengers ;)

Dieter Rencken (@dieterrencken)

24th January 2019, 5:15

It’s also a flat race for horses held in Tipperary – but, like your example, it’s a name not a definition.

BasCB (@bascb)

24th January 2019, 13:35

:-D

Dave F. (@dave-f)

27th January 2019, 19:38

Concord is the translation of concorde. Agreement is a synonym.

Aleš Norský (@gpfacts)

23rd January 2019, 13:31

Many people disliked Balestre, yet nothing and nobody could prevent him becoming the FIA president in 1985. Wasn’t the 1981 SAGP argument also largely about the aerodynamic rules (side miniskirts in particular) that FISA banned post 1980 and the garagistas wanted to keep? All cars taking part in that race had them…hence the Formula Libre designation.

maiagus

23rd January 2019, 15:24

Why can’t we have beautiful cars as this Brabham?

What did we gain with the last years’ “aero development”?

RogerA

23rd January 2019, 15:45

Performance which is what F1 is supposed to be about.

I much prefer the more modern cars to the older one’s because they look fast, they look complex & technical which for me is what separates & puts f1 above everything else.

the old cars looked good for there time but they look far too basic now, they look like junior formula cars compared to the top tier pinnacle of the sport which f1 cars should look and perform like.

and also worth maybe remembering that at the time many fans were complaining that those cars looked bad and the cars from the 50s/60s and such looked better. it’s all subjective and also a lot of rose colored glasses where things are always better in the past.

it is actually interesting how watching the f1tv archive lately there are many races from the early 1980’s in which there is not a lot of overtaking and the commentators discuss how hard overtaking is in f1 and how some think there is not enough. yet today we look back at those times as been what we want to go back to with ground effects and all the overtaking there was then, when in fact the f1 back then was not really different to today. cars could follow a bit closer but overtaking was just as difficult as this archive shows and commentary confirms.

Robbie (@robbie)

23rd January 2019, 16:42

Sure there will always be a percentage of people that liked how it was before etc etc, but when I look at pictures like these 80’s cars I remember that they were the cutting edge at the time. I don’t look at them as basic junior formula cars, because they were not.

I also think that a certain percentage of people want to see more overtaking, but many fans who have been intimate with F1 over the decades appreciate that F1 has always wanted their passes to be less frequent than moreso…rare and difficult so that they are memorable and spoken of for decades to follow. The opposite of that would be the drs passes that are not rare, nor memorable for even a few minutes past their occurrence, let alone a few decades.

For me it is about the flavour of things. I have never minded passes being rare and difficult when we are also seeing the art of defending taking place. That goes out the window with drs. What Liberty has talked about is to me more in line with what F1 has been and should be. No drs, tires that can handle a car following closely in dirty air, cars less sensitive to dirty air, and thus closer racing…but that doesn’t have to mean by default umpteen passes per race and a bit of a lottery as to the winner. Nobody is saying they want that for F1, at least nobody within F1 that matters to it’s future, at least not that I’m aware of anyway.

Whatever F1 has been in the past, and whatever fans’ opinion is, rose-tinted glasses or not, imho F1 should be about gladiator vs gladiator on the track, attempting passes, defending, but not sitting there being told what lap times to run in order to optimize a computer model that a satellite group not even at the race has determined is optimum to win the race. Back to some basics that put more of the driving in the drivers’ hands, please. At least in the past when there was difficulty overtaking one had more of a sense that the outcome was in the drivers’ hands, not the fate of the tires or the computer model getting it right, nor with the assistance of drs.

mmertens (@mmertens)

24th January 2019, 0:03

Wow, I couldn’t have phrased that better, you are totally spot on regarding what is needed at F1. I fully agree.

anon

23rd January 2019, 19:34

RogerA, as you say, there is a difference between what people may remember about those races and the reality of how those races actually played out. The human memory is rather fickle and malleable and is prone to creating false memories of an event that we believe should have happened, or adjusting memories to fit a particular perception of how we want to remember things.

Picking up on one theme, there is a disconnect between the memories people have about overtaking rates in the past and what actually happened during the races. There is a perception that there was a lot more battling and overtaking on track in the 1980s, but when you look at the statistics, the average amount of overtaking went into a pretty persistent decline after 1984.

The perception is out of line with reality, perhaps in part because people tend to remember the races where there was more action and, with their memories being biased towards those events, create a false impression for themselves that those races were the normal state of affairs, rather than being exceptions and that the races were often more processional than they think they were.

Equally, there are perhaps false perceptions about how much fuel and tyre saving went on in the 1980s and about how much radio traffic there was between the pit lane and the drivers. The TV broadcasts of the time did not have access to that data and, as the commentators did not draw attention to it, there is perhaps the perception that sort of management was absent from the sport.

However, if you read through some of the articles that were written at the time, you realise that fuel and engine management was a rather important part of racing at the time, and that often the drivers were having to race to pre-planned lap times based on the calculated fuel consumption from the onboard computer systems – here’s an example from Motorsport Magazine’s report on the 1986 German GP:

“That Senna (Lotus-Renault), Rosberg (McLaren-Porsche) and Prost (McLaren-Porsche) could do nothing about Piquet and the Williams-Honda could be put down to engine management and fuel-consumption. All three were being forced to drive slower than they are capable, simply because their cockpit fuel metering recording device was warning them that if they went any faster they would use up their 195 litres of fuel before the finish.

[…]These Formula 1 Fuel Economy runs are fun to watch, providing you don’t know what is actually going on in the cockpit or over the pits-to-car radios, and when it was all over one had to admit that the paddock had been more fun than the race track. Perhaps we should all sit around in the sun and write Press Notices or spread rumours, rather than put on the farce that Grand Prix racing has become.”

However, people tend to gloss over or forget the involvement of technology in that era and seem to have a perception about the importance of the drivers that is perhaps disproportionate to the role that they played at the time.

@HoHum (@hohum)

23rd January 2019, 22:08

I wonder ANON, if your analysis would hold true for the 1.5 and 3 litre era of the 1960’s, I doubt it, but maybe that’s just my RTspecs.

mmertens (@mmertens)

24th January 2019, 0:22

And let’s also not forget that in these 80s races we had team mates that had same cars with the same information and fuel consumption that managed to optimize their results using their skills to decide where to short rev when changing gears, playing with different gear ratios, etc in order to sabe fuel and finish races, and this is also for me a sign of a great driver. It’s the skill to know how and where to be aggressive that always counted. And this regardless of the era . f1 races always had car management as a key component, from Caracciola and Nuvolari until today. The only thing that devalues this aspect nowadays is that everything is analyzed by hundreds of engineers remotely in real time using all kinds of algorithms to find the optimal strategy., devaluating the skill needed from the drivers.

Duncan Snowden

23rd January 2019, 15:56

“Grandee”. Two “e”s.

But I’m nitpicking. It’s fascinating stuff. I’ve always been intrigued by this era since it was around the time I started becoming interested in F1 (perhaps a little earlier), but was too young to really understand what was going on. And, of course, it set the stage for what the series became.

Nick Wyatt (@nickwyatt)

23rd January 2019, 17:07

@Duncan Snowdon, no Dieter is correct. The term ‘Les Grandes’ was used by Balestre to distinguish between the large manufacturer teams (Renault, Ferrari) and the smaller independent teams who were dismissed as ‘garagistes’.

The term ‘Grandee’ in English normally refers to a senior politician with a lot of influence and has little to do with the subject here.

Duncan Snowden

23rd January 2019, 18:37

Fair enough if he’s directly quoting Balestre. But they were known as the “grandees” by the “garagistes” and in the British press. Murray Walker was still calling Ferrari “one of the grandee teams”, although by that time he was using it as a synonym for a works engine deal, into the ’90s.

GeeMac (@geemac)

23rd January 2019, 16:10

Great read @dieterrencken. Would you be able to make more pages from the WFMS/WPDC documents available?

On a (sort of) related note: I’m reading the recent Pironi biography and happen to be at the bit dealing with the GPDA strike at Kyalami in 1981. The author suggests that Pironi played a big role in those negotiations, acting as the liaison between the drivers the teams, but I was always under the impression that Niki Lauda took the lead of these negotiations even though Pironi was the chairman of the GPDA at the time. Do you have any insight into that?

Dieter Rencken (@dieterrencken)

23rd January 2019, 19:03

I’m sure you’ll understand that publishing papers I haven’t used yet reduces my ability to use them in future – particularly given the ‘theft’ of editorial material that is currently prevalent. In fact it was the subject of one of the tweets in the Roundup earlier today. But I can assure you that the papers are too intriguing to keep hidden…

Re the drivers strike: it was 1982 not 1981 or it would have coincided with the rebel GP in this article.

While Pironi was GPDA chairman and led the discussions, Niki had originally flagged up the contractual issue and was the most vocal. As the returning hero and a driver with a short-term deal – he’d promised Mclaren he’d walk if he couldn’t prove himself with 4 races – he had both the stature and the least to lose.

Sven (@crammond)

23rd January 2019, 23:44

In retrospect, what was then named FIASCO now looks like a highlight of F1-history. Not because of the outcome, but because of the entertaining nature of the events themselves and the participating individuals. Will F1 ever get something like Bernie vs Balestre again? Probably not.

DB-C90 (@dbradock)

24th January 2019, 1:13

Great article. If the quality of articles (and the new innovations) we’re seeing so far this year is any indication, we are in for a great season from my favourite web site.

Fantastic work @dieterrencken, @keithcollantine – May your site rule supreme

Jimmi Cynic (@jimmi-cynic)

24th January 2019, 7:18

@dbradock: Hear Here.

Glennb

24th January 2019, 3:22

“There are only four parameters which control the performance of a racing car:

a) the engine power available

b) the aerodynamic download which can be generated

c) the area and effectiveness of tyre rubber in contact with the ground

d) the weight of the vehicle”

I would argue that:

e) the ability to pull up said racing car

is worthy of consideration as a performance parameter…

Silfen (@silfen)

24th January 2019, 18:58

Great story, tbat brings back memories from long ago. Thank you for these insights @dieterrencken.

Alianora La Canta (@alianora-la-canta)

25th January 2019, 20:05

This is a thoroughly enjoyable explanation of how modern F1 got started. Thank you very much, Dieter and Forrest, for helping us understand how we got here from there (the 1970s).