During the mid-nineties Royal Dutch Shell found itself embroiled in a series of enormous reputational tangles. The energy giant was under siege from environmental activists such as Greenpeace and Friend of the Earth over its policy of leaving decommissioned oil rigs in location rather than dismantling them, and plans to scuttle its giant Brent Spar rig in the North Sea.

At the time Shell, with shared head offices in Amsterdam and London, was the biggest company in Europe and comfortably inside the global top 10. But it also stood accused of collaborating in human rights abuses in the Niger Delta, where tribal leaders protested against alleged indiscriminate petroleum waste dumping by exploration companiesIn response, pan-European boycotts of Shell were called for. Sales at branded filling stations dropping dramatically, particularly in Germany, where the green movement was arguably strongest. Nonetheless, the brand enjoyed one of its highest market penetrations in the region, with one in every seven service stations displaying the distinctive red/yellow sea-shell logo.

The backlash grew. By early 1995 Shell fuel outlets were being firebombed and Germany’s premier Helmut Kohl lodged formal complaints with British prime minister John Major over Brent Spar. Human rights activists grew increasingly vociferous after the execution of Kenule ‘Ken’ Saro-Wiwa, a Nigerian author and activist who was executed in Nigeria following his protests.

Although Shell eventually succumbed to pressure and reversed its decision to sink the rig, and reached a $15m settlement with Nigerian tribes without admitting liability, enormous damage had by that stage been inflicted on the brand. Clearly Shell needed to react rapidly or face further commercial and reputational fallout.

The Scuderia also faced losing its fuel and oil sponsor Eni, parent of Agip – they of the distinctive fire-belching, six-legged dog logo – which was gearing up for an initial public offering at the time. Schumacher had won the 1994 championship for Benetton and was well on his way to a second, leading manager Willi Weber to make astronomical demands in exchange for the services of the only world champion in the sport at the time.

Marlboro had dropped McLaren and switched its F1 funding solely to Ferrari, but more money was needed. The solution was logical: Shell returned to F1’s legendary team as a technical and commercial partner, in turn benefitting from an association with Schumacher, then emerging as Germany’s darling sports personality and on his way to challenging Senna in F1’s popularity stakes.

Shell and Ferrari had history – they entered the world championship together in 1950 – but the latest deal took their relationship to new heights. Schumacher fronted a series of Shell television commercials, so much so that he seemed to be spending much of his off-seasons in front of the cameras. But he also delivered on-track, culminating in an unprecedented run of five consecutive titles.

Equally, Shell’s emblem received prominent placements on the scarlet cars and was embroidered on all production worker overalls. Global advertising campaigns trumpeted the relationship, with trackside hoardings at Ferrari’s Fiorano test facility bearing Shell’s logo.

If this was sponsorship at its most visible and enduring – the partnership continues to this day despite Schumacher’s first retirement in 2006, only to make a three-year return with Mercedes and Petronas – it was also an example of what has come to be known as “sportwashing”. The term is usually applied to venues holding major sporting events, but the principle is the same: the cleansing of a brand’s image via an emotive association with, in this case, F1.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Today questions of environmental sustainability and pollution are ever more pressing. And the positive associations to be found in Formula 1 are just as alluring.

That being, of course, Lewis Hamilton, who has become a vociferous champion of environmental causes in recent years.

Ineos’s chairman and major shareholder Sir Jim Ratcliffe, who founded Ineos by buying up BP’s petrochemical assets and has since amassed sufficient wealth to challenge for the title of ‘Britain’s Richest Man’, spoke of being at “the forefront of technological innovation and human performance”, and of “grit and determination to redefine what is possible” as reasons for the partnership.

The man who has committed an estimated $150m to the team added he had only met “Lewis – and his dog – for five minutes, so I don’t know him, but I am a great admirer.”

The company sprang to prominence last year when it sponsored the Ineos 1.59 Challenge, in which Eliud Kipchoge became the first person to complete a marathon distance in under two hours. In 2018 Ineos announced plans to contest the 2021 America’s Cup. Its other recent sporting property acquisitions include the former Team Sky cycling team (April 2019), and the French football ligue club OGC Nice (August 2019). Quite a shopping spree in just two years.

Ineos, with an annual turnover measured in tens of billions, is believed to be paying around $30m per year for its links to Mercedes. It boasts that its products are found in applications ranging from “paints to plastics, textiles to technology, medicines to mobile phones”. It plans to leverage the partnership via a variety of activities, including flashing its red logo on the airbox, directly above the F1 drivers’ helmets.

One can only imagine how Hamilton will feel every time he steps into his car and slides into the custom moulded seat mounted directly below the red logo. This is the man who in Mexico spoke fervently about his environmental beliefs and lifestyle.

“I’m trying to make sure that by the end of the year I’m carbon neutral,” he told the media. “I don’t allow anyone in my office [and] also within my household to buy any plastics. I want everything recyclable down to deodorant, down to toothbrush, all these kind of things so I’m trying to make as much change as I can in my personal space.”

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Hamilton embraced veganism three years ago as the “only way to truly save our planet” and admits to being worried “where this world is going”. That Thursday in Mexico he talked about the sustainability of his fashion range, his push for car makers to move away from leather car interiors – referencing Mercedes in the process – and the need to switch to biodegradable water bottles.

“You can always improve,” he continued. “I think a simple thing like plastic bottles, I’m sure if we all agreed that there’s no plastic bottles or no plastic allowed in the paddock that can go a long way.”

Plastics of the variety produced by Ineos at the rate of 300 billion pellets per week at one plant alone, are said to be a major contributor to ocean microplastic pollution. Last year the BBC documentary “War on Plastic” turned focused public concern over plastic production on, among others, Ineos. A quick search of news sites, including New Scientist and Financial Times, shows dozens of allegations levelled against the company and its subsidiaries, and not only in the United Kingdom.

Here, then, is a company in need of a major image burnish, which measures its profits in tens of billions, making its estimated $150 million spent over five years on Mercedes look like petty cash in comparison.

Mercedes motorsport boss Toto Wolff said the deal “is an important cornerstone of our future plans in Formula 1 [which] once again serves to demonstrate the attraction of the sport for ambitious, global brands with a long-term vision for success.” But it’s hard not to see it as a more simple exchange of cash in return for image varnishing, particularly as Wolff has admitted a desire for the Mercedes F1 operation to be cost neutral.

Given that F1 revenues cover, at best, 50% of a team’s operating budget, clearly the balance needs to be raised either from commercial streams, preferably from partners, thereby reducing the current reliance on the parent company – much as Ferrari does, which funds its F1 programme through partnerships.

One wonders what the Mercedes main board, currently wrestling with the question of sustainability, makes of the partnership, particularly as Mercedes’ compliance code requires that “direct suppliers all over world comply with our sustainability standards”. Does that code not apply to any direct supplier of $150m?

But Ineos is only the newest example of a conundrum being grappled with throughout F1, and not only within teams: How to balance current and future income streams in the face of plans for the sport to have a to have a net-zero carbon footprint by 2030. That target is a big ask for a sport whose participants have currently or previously engaged more than half of the world’s 20 largest polluters. Ineos does not even feature among these names, which account for one-third of the world’s carbon emissions according to data recently compiled by The Guardian.

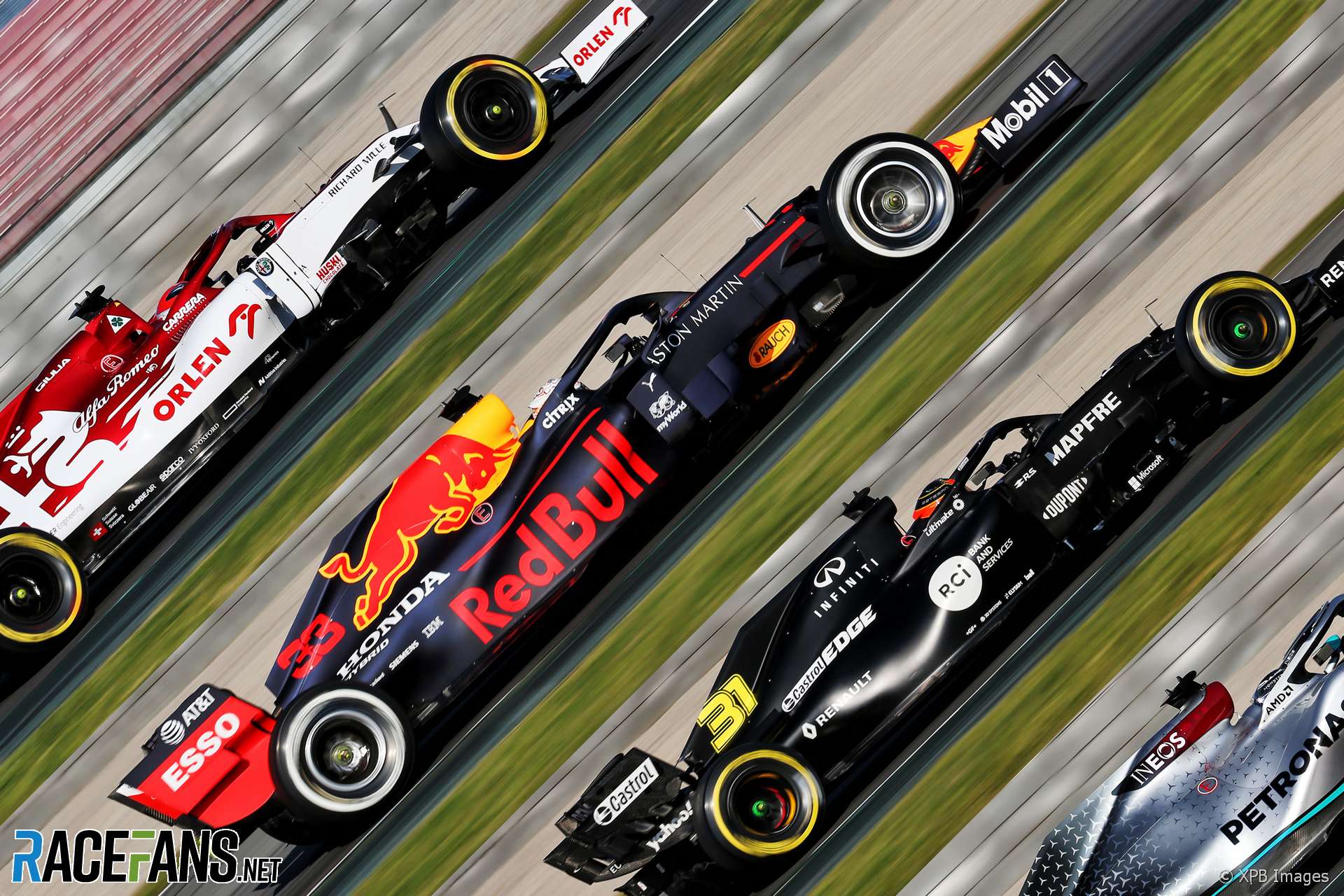

Saudi Aramco tops the list, Red Bull sponsor ExxonMobil is fourth place, Renault partner BP sixth and Shell next. And sources within F1 have admitted that the sport is eyeing a race in Saudi Arabia within two years, with the event to be generously funded by – you guessed it – Aramco…

One of the cornerstones of F1’s sustainability plan is to “use only recyclable or compost-able materials [i.e. eliminate single-use plastic], and ensure that 100% of waste is re-used, recycled or composted” by 2025. Yet the sport holds no sway over the commercial interests of the teams, just as F1’s authorities were powerless to act during the tobacco years until global legislation (largely) outlawed such marketing activities.

Could it be that companies such as Ineos, feeling the weight of public opinion turning against them and aware that polluting products and practices will increasingly be targeted by legislators, are increasingly turning to F1 as a last-ditch image-polishing pedestal, just as tobacco companies used F1 and alcohol brands are currently availing themselves of?

The FIA already operates a sustainability certification programme, but this applies only to teams and not their suppliers or partners. Some form of regulatory intervention is therefore required.

F1’s future lies not with a fossilised fan base but with a vibrant, young following. The latter generation abhors the waste of its elders, and rebels fiercely against unsustainability: real, perceived or looming. Accordingly, F1 as both a sport and a global business needs to introduce an enforceable code of conduct and sustainability for its teams and their partners, all of whom would need to sign up as a condition of entry.

All that will, of course, take time – but, equally, time is running out for a sustainable future for F1. In the interim we are, though, unlikely to see Hamilton or Russell extolling the virtues of single-use plastics in TV commercials, regardless of how much Ineos pays.

RacingLines

- The year of sprints, ‘the show’ – and rising stock: A political review of the 2021 F1 season

- The problems of perception the FIA must address after the Abu Dhabi row

- Why the budget cap could be F1’s next battleground between Mercedes and Red Bull

- Todt defied expectations as president – now he plans to “disappear” from FIA

- Sir Frank Williams: A personal appreciation of a true racer

Aleš Norský (@gpfacts)

19th February 2020, 13:28

It is not necessarily up to (any) sport to save the planet, only the politicians can force, through regulation, the companies to be more environmentally responsible, recapturing their own used products for recycling, etc… Which, of course, would reduce profits, so there is zero appetite for that on both sides. That does not mean that F1 or anybody else should not do their part…but the truly global change that is needed can only come through implementation of environmentally sustainable policies by all world governments.

Chris (@raidpw)

19th February 2020, 14:13

And the only way politicians will push that sort of legislation through is by it being a vote winner. The only way it’ll be a vote winner is if the voters care about it enough. The only way voters will care enough is through awareness, and that’s where sport (among other things) comes in.

anon

19th February 2020, 19:41

@raidpw the problem being that, as is noted in this article, the tendency is for companies to use sport to clean their public image in an effort to make them look better.

Ineos, as it happens, has a fairly poor environmental record – the Seal Sands arcrylonitrile factory alone racked up 176 pollution incidents between 2014 and 2017, with the Environment Agency formally complaining that the air pollution from that factory was “well over the legal limits”. The response of Ratcliffe? He sent a letter to the business secretary which was basically a blackmail threat – demanding that either he be allowed to not comply with the law, or he would fire everybody and shut the factory down because he apparently “couldn’t afford” to upgrade the factory.

In a 12 year period, they had 24 prohibition notices from the Health and Safety Executive – the most serious penalty they can issue, as that requires a breach in safety regulations that is so serious that the company has to immediately cease all operations at that facility – and, in 2014, one factory saw 23 workers hospitalised due to severe chemical burns in two major spillages.

Some might note it is rather strange that Ineos claimed that it can’t afford to comply with legislation or, when instructed by MI5 that Ineos’s lack of security measures presented a major threat to the UK’s infrastructure, also claimed that it couldn’t afford to pay for security upgrades, but can afford to spend money on sponsoring teams and sports events.

As an aside, Dieter Rencken is actually wrong to state that there is no indication that Ineos hasn’t committed human rights abuses. In 2019, there was a legal case – Boyd & Anor v Ineos Upstream Ltd & Ors [2019] – after Ineos applied for injunctions against “persons unknown”: the purpose of the injunctions was to stop everybody in the UK from making any form of protest at any Ineos facility.

As it happens, the case was eventually heard in the Court of Appeal, which ruled that Ineos’s application was a gross violation of the Human Rights Act as the terms of the injunction they sought were so wide ranging as to effectively seek to ban all forms of legal protest against Ineos.

Fer no.65 (@fer-no65)

19th February 2020, 21:30

I always find this generalisation that young people care fiercely about environmental issues quite interesting, if not a bit funny…

Jay Menon (@jaymenon10)

20th February 2020, 0:14

Capitalism and Sustainability….(looks up term Oxymoron in dictionary)

maiagus

20th February 2020, 0:37

AS I’ve said on a early comment, as internal combustion cars were banned in some countries/locations, oil companies sponsorship might also be banned.