This week 40 years ago, an Italian fashion label signed a deal which began one of the most successful, influential and colourful sponsorship programmes in Formula 1 history.

Benetton’s entry into F1 with Tyrrell was successful from the outset, but the brand aspired to do more than just put its stickers on an F1 car. Within three years it had a team of its own and was winning races as a constructor, and in time it enjoyed championship-winning success with one of F1’s all-time great drivers.

The idea a brand that was ‘just a T-shirt manufacturer’ could succeed in F1 was greeted with scepticism with some on their arrival. But Benetton soon disproved the doubters and inspired other brands to do the same – notably the soft drink producer which goes into the 2023 season as defending champions.

1983: Tyrrell

Plucky underdogs Tyrrell had Denim logos on their cars when Michele Alboreto won the 1982 season finale at Las Vegas. But Luciano Benetton refused to share space on their car with them, so Tyrrell ended its deal with their rival and painted their cars green for 1983.

In only the seventh race with Benetton as a sponsor Alboreto delivered another win, in Detroit. However it proved the final win for the former champions, and for the following season their Italian sponsor had their eye on a manufacturer closer to home.

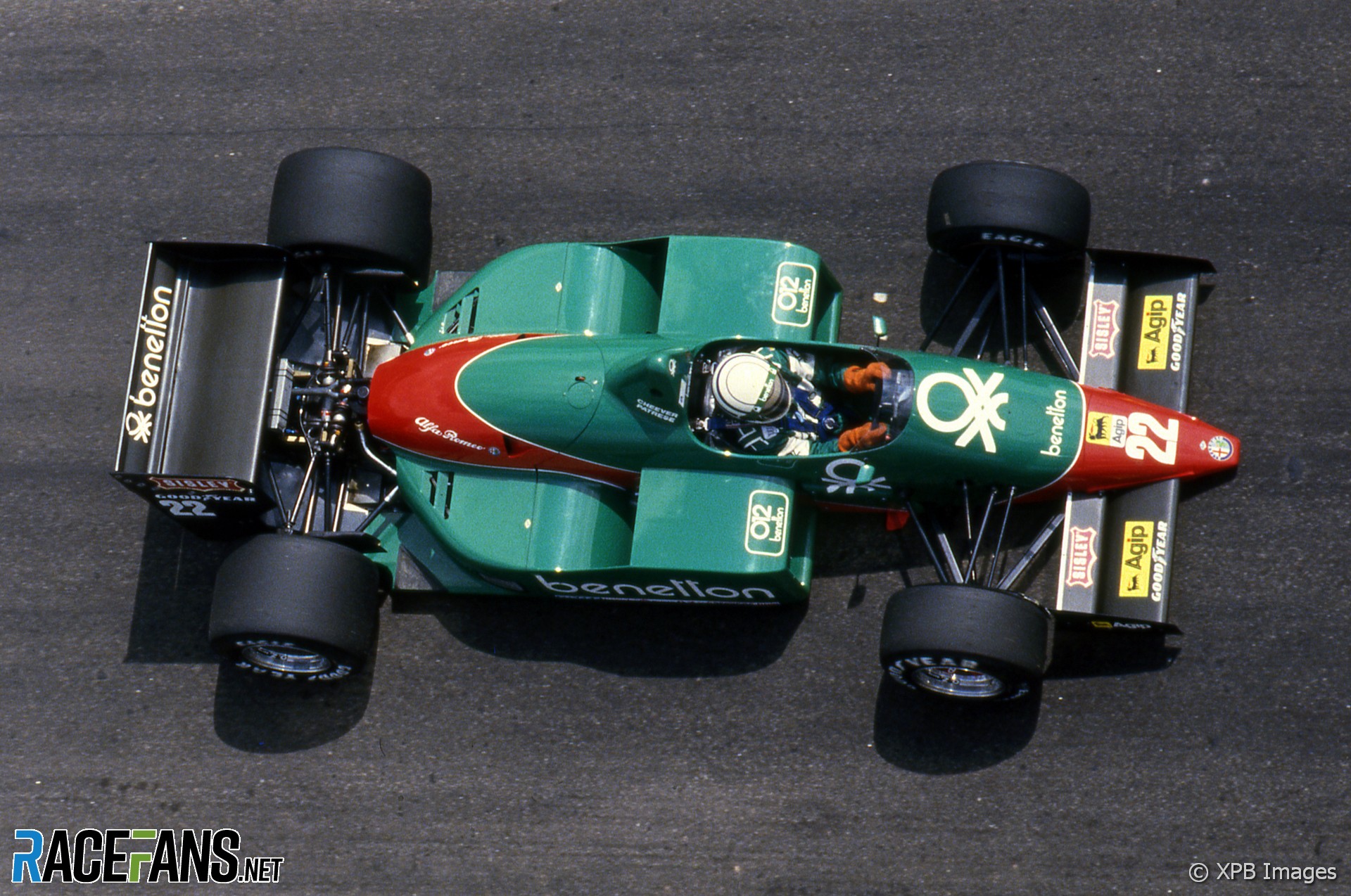

1984: Alfa Romeo

Alfa Romeo’s F1 team, run by Euroracing, successfully courted Benetton as a replacement for outgoing sponsor Marlboro. But from sixth in 1983 they slipped two places the following year, though they took a single podium finish in the home event for team and title sponsor at Monza.

1985: Alfa Romeo and Toleman

It wasn’t enough to avoid a point-less campaign for the team. While Benetton opted to move elsewhere, Alfa Romeo quit the sport and did not return until they started sponsoring Sauber in 2018.

Instead Benetton threw its backing behind Toleman. There was clear potential in the team which had enjoyed podium finishes and nearly a win in 1984 with Ayrton Senna. Although it also ended 1985 point-less, having missed the start of the season for the bizarre reason of being unable to source any tyres, Teo Fabi took pole position at the Nurburgring.

In Toleman, Benetton had found not just a team to sponsor, but to take over and run the way they chose.

1986: Benetton Formula

Did a T-shirt manufacturer know what they were doing running a racing team? An astute move by Luciano Benetton soon after their takeover of Toleman indicated they did. Their former relationship with Alfa Romeo pointed an obvious path to an engine supply, but Benetton instead did a deal with BMW for their potent turbos.

It paid off on F1’s quickest tracks where the B186s, decked out in the United Colours of Benetton, were at their most competitive. Gerhard Berger delivered an early podium on home ground at Imola. Fabi took back-to-back pole positions at the Osterreichring and Monza.

Then in the penultimate round at the Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez in Mexico, Berger managed his Pirelli tyres to perfection and gave Benetton a victory in their first season.

1987

Benetton reacted quickly when BMW made the unexpected decision to cancel its F1 programme during 1986, and secured an exclusive deal for Ford engines. The cars were presented in a plain livery, before the team introduced a new look based around its green colouring incorporating attractive flashes of different shades.

Having lost Berger to Ferrari, Thierry Boutsen joined for what proved a winless second season, though they moved up a place to fifth in the constructors championship.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

1988

In the final year of F1’s ‘turbo era’, Ford made an early switch to normally aspirated power in preparation for the coming season. Rory Byrne, the designer who’d been with the team since the Toleman days, produced an effective and reliable design in the B188 which delivered seven podiums for Boutsen and new team mate Alessandro Nannini and a new high of third in the championship.

1989

Williams hired Boutsen, so Benetton paired Nannini with Formula 3000 star Johnny Herbert, who had been badly injured at Brands Hatch the year before. Despite a brave fourth place on his debut, Herbert remained in considerable pain from his injuries and was dropped mid-season. In his place came Emanuele Pirro, who had missed out on a chance to drive a third Benetton as a customer entry in 1987 when the project ran afoul of FIA rules.

The most significant personnel change occured at the top of the organisation, however. Seeking better results after two winless seasons, Luciano Benetton made a surprising appointment in charge of his F1 team: His former North American business head Flavio Briatore, who admitted he knew nothing about motor racing.

The team returned to winning ways at the end of the year, albeit in controversial circumstances. Nannini finished second on the road to Ayrton Senna at Suzuka, but the McLaren driver’s disqualification earned the Benetton driver his first victory and the team’s second.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

1990

Briatore made two major hirings for 1990. John Barnard arrived from Ferrari to take over car design and three-times world champion Nelson Piquet was hired from Lotus.

Nannini showed up well against Piquet early in the year, but his F1 career was ended in October by a helicopter crash which severed his arm. Roberto Moreno was hired as his replacement. Benetton again benefited from controversy in Japan to win, Piquet taking his first victory for three years, which he repeated at the season finale in Adelaide.

1991

Those wins were also the final time Benetton’s cars appeared chiefly in their own colours, as they courted other sponsors to foot their team’s growing bills. First up was the RJ Reynolds tobacco company whose Camel brand had been associated with Piquet at Lotus.

Barnard’s B191 arrived at the third race of the year and won the fifth round, in Canada, though Piquet’s final win was the team’s only victory of the year, and its designer left the team three days later following a long-running dispute with the team’s management. Meanwhile Tom Walkinshaw bought into the team.

At Monza Piquet suddenly had a new team mate. After Michael Schumacher impressed on his debut for Jordan at Spa, Bernie Ecclestone urged his friend Briatore to sign him up. Schumacher was controversially prised away from Jordan and Moreno booted out of Benetton to make room for him. But the hiring was immediately vindicated: Schumacher scored points-scoring top-six finishes in his first three starts for his new team.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

1992

Though the team had lost Barnard, several other notable figures had left and returned in the preceding 12 months, including Byrne, Pat Symonds and Willem Toet who temporarily joined Reynard’s aborted F1 project. Gordon Kimball continued work on Benetton’s latest car in the meantime. The new B192 took the raised nose concept of its predecessor even further, starting a trend other teams would follow.

There were more significant changes behind the scenes in October as the team moved into its new base at Enstone – still home to its successor, Alpine. Benetton was assembling a team capable of eventually taking the fight to the likes of Williams, who dominated the season with their revolutionary FW14B.

Schumacher scored a breakthrough win at a damp Spa 12 months on from his arrival in F1. He was clearly the team’s future, while Martin Brundle was consigned to its past after a single season despite a consistent year. The team fell short of beating McLaren to second in the constructors championship by just eight points.

1993

Benetton’s rivalry with McLaren intensified the following year as both had Ford Cosworth engines, though McLaren’s were one development step behind to begin with. Riccardo Patrese arrived from Williams to take Brundle’s vacated seat but he couldn’t live with Schumacher’s astonishing speed either. He retired at the end of the year as F1’s most experienced driver at the time.

While Schumacher took a single win, the team came in third behind McLaren again. But a major change in the rules was about to play into their hands. Meanwhile as RJ Reynolds called time on their involvement in F1 Benetton sourced another cigarette manufacturer – Japan Tobacco – to take over as title sponsor with its Mild Seven brand, prompting another change of colour scheme.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

1994

Heading into 1994 the FIA banned a host of technologies which Williams had perfected in their all-conquering cars of 1992 and 1993. Benetton got their new B194 sorted early and Ross Brawn’s strategists were quick to master new rules which permitted in-race refuelling. Schumacher out-ran Senna to win the season-opener in Brazil, then followed it up with another win at TI Aida. Senna, eliminated early, became an interested spectator, suspicious of whether Benetton had truly expunged all forbidden technologies from their car.

At Imola the championship and the F1 world changed forever when Senna, leading with Schumacher in pursuit, crashed and was killed. A shaken Schumacher was now the title favourite, and after seven races he had six wins plus a second place achieved despite being stuck in fifth gear.However a spate of controversies over the second half of the year limited Schumacher’s points-scoring and brought Damon Hill into the title fight. They went into the finale separated by a single point, and Schumacher sealed the championship in controversial circumstances after clashing with his rival.

Benetton had won eight races, all courtesy of Schumacher, and taken a driver to the championship for the first time. However they had missed out on the constructors’ crown, partly because the second car had cycled between JJ Lehto, Jos Verstappen and the returning Herbert over the course of the campaign.

1995

Benetton’s successful association with Ford ended as the team seized the opportunity to use the same Renault V10s as reigning constructors champions Williams. The objective of adding the team’s title was achieved as Schumacher took nine more wins and Herbert was on hand to pick up two more on two occasions when his team mate went out in collisions with Hill.

Had Schumacher remained at the team in 1996 he would have been a strong contender for a third consecutive drivers’ title. But the lure of Ferrari proved too strong. Herbert, who learned early in the year not to expect to see much of his team mate’s data, was also shown the door, meaning the champions had an all-new line-up for 1996.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

1996

Not only did Benetton fail to defend their title in 1996, neither new driver Jean Alesi nor the returning Berger managed to win a single race. Meanwhile several top team staff were tempted to follow Schumacher to Ferrari: Brawn decided to move on and was soon joined by Byrne.

1997

Berger delivered a final hurrah for Benetton midway through 1997. The driver who scored their first F1 win also took their last, at the Hockenheimring, at what was otherwise a tough season for the 38-year-old driver heading into retirement. He missed several races due to illness and stand-in Alexander Wurz impressed, winning a full-time drive for the following year.

Another threat to Benetton’s performance emerged, however: Renault called time on its multiple championship-winning engine programme, leaving Benetton without a manufacturer engine supply. Briatore was also gone, stepping down late in the season, replaced by Prodrive’s David Richards.

1998

Drastic new aerodynamic regulations were introduced for 1998, forcing teams to build considerably narrower cars. Benetton appeared to have anticipated the changes well and got their new B198 running early. However McLaren blew the competition away with their MP4-13, allied to a timely switch to Bridgestone tyres. Wurz was joined at the team by Giancarlo Fisichella, who Briatore also managed.

Benetton continued using Renault’s engines as customer, and branded the Mechchrome units as ‘Playlife’, a new extension to its sportswear brand. However they were increasingly outgunned by the manufacturer-backed Mercedes and Ferrari engines, and their competitiveness dwindled over the coming years. Fifth in the championship was their lowest finish in more than a decade. Fellow ex-Renault users Williams soon agreed a deal with former Benetton supplier BMW, who targeted a return to F1 in 2000.

There was another change at the top of the team, as Richards left within a year and Rocco Benetton installed in his place.

1999

Seeking to claw back some of their lost performance, designers Pat Symonds and Nick Wirth devised an innovation known as “Front Torque Transfer” for the B199, intended to improve the car’s cornering. However any benefit gained as a result of the weight it added to the front end of the car was insufficient, and it was soon removed.

The team continued its slip down the order, scoring just 16 points all year. Wirth departed at the end of the year, and rumours mounted that Benetton was looking for a way out of F1.

2000

Just two years after leaving F1, Renault decided it wanted to return. Five days after the 2000 season began, the manufacturer confirmed it would take over Benetton. However the rebranding would not take effect for two more years, during which time the Benetton name remained.

Fisichella delivered second place at the next race in Brazil, giving Benetton an early uplift in the 2000 championship. It ended up proving decisive, as they ended the year tied for fourth place in the points with BAR, and Fisichella’s podium made the difference which put Benetton ahead.

2001

For the final year of Benetton, Renault produced a novel, 110-degree V10 engine. It did not provide the breakthrough they needed, and the team lacked pace and reliability for much of the season. Only in the latter part of the year did it finally start to come good, and Fisichella delivered Benetton’s final podium finish at Spa. New team mate Jenson Button laboured to a distant 17th in the championship.

They lined up for Benetton’s final race at Suzuka, where the team scored three of its 27 wins, inside the top 10. Fisichella retired with six laps to go while running just outside the points in seventh, promoting Button in his place to score the final finish for Benetton in F1.

F1 history

- How you rated F1’s 12 sprint races so far – and why two outscored the grand prix

- Alonso set to become F1’s oldest driver for more than 50 years

- From ‘Flying Pig’ to Senna’s heroics: The short, incredible history of Toleman

- From farcical to fantastic: Formula 1’s 14 title-deciding Japanese races ranked

- Benched: The five other drivers who stood down for team mates in last 50 years

Qeki (@qeki)

12th January 2023, 15:43

My first memories of Benetton were somewhere between 1999-2000. For me they were the midfield Minardi. I liked them and my I mostly chose them in F1 2001.

Is there any other team which has the same driver winning teams first and last race and to have someone else winning in between?

AndrewT (@andrewt)

12th January 2023, 18:17

@qeki: Only two other occasions come to my mind.

– Maserati: 9 wins, first win in Monza 1953, last win Nürburgring 1957, by Juan-Manuel Fangio, and Stirling Moss scored twice between the two

– Vanwall: 9 wins, first win in Aintree 1957, last win Ain-Diab 1958, the latter one was won by the very Stirling Moss that was involved with Maserati above, but the former win was scored by Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks sharing drive, and Tony Brooks is the driver scoring multiple victories between the two.

Qeki (@qeki)

12th January 2023, 19:47

@andrewt Thanks for the info!

DanielH (@danielh)

13th January 2023, 10:48

BrawnGP probably count….Button was their first and last driver to win a race with Barrichello in between. Sort of?

skydiverian (@skydiverian)

14th January 2023, 1:30

@danielh Brawn doesn’t count. Jenson won 7 of the first 8 races but didn’t win again. Rubens 2 wins came after all of Jenson’s, at Valencia and Monza.

amian

12th January 2023, 18:17

I love their shark nose design that they had in 1991-1998 (maybe not so great looking in the last year).

When I started following F1 around 1992, the yellow-green painted Benettons with those shark noses were my favourite cars.

AndrewT (@andrewt)

12th January 2023, 18:22

@amian: Interestingly enough Benetton’s successor Renault re-adopted those nose designs on their 2009 and 2010 challengers as well.

Nick T.

12th January 2023, 18:45

They’re just a t-shirt company. They can’t win! They’re just a fizzy drinks company. They can’t win. Oh, McLaren and Ferrari, you poor fools.

F1 frog (@f1frog)

12th January 2023, 18:57

Michael Schumacher’s world championship for Benetton in 1994 is probably the most controversial of all time (although 2021 came close). The Adelaide incident with Damon Hill wasn’t proved to be deliberate, but I think what happened three years later with Villeneuve in Jerez made it seem very likely that it was. And Benetton were also accused of cheating in many different ways during the season, most seriously with the illegal traction and launch control code which was available on the car but hidden, supposedly to prevent the drivers accessing it by accident. It was never proved that Benetton had actually used it, just that it was available, so they got away with it, but considering they also cheated by removing the filter on a refuelling rig to speed up pitstops and raced with a plank that was ‘excessively worn’ in Spa in order to reduce the ride height (which they were disqualified for), and the fact that the FIA bothered to look in the first place because they were suspicious of Schumacher’s quick starts, I find it hard to believe that Benetton weren’t using launch control. Damon Hill really should be a double world champion.

It’s quite a clever way of cheating, though, unlike spending more money than you are allowed and getting away with it by convincing the FIA that it wasn’t deliberate, and because the rulebook has been written so poorly that you can escape with just minor punishment, but I sort of agree with the Spartan way of thinking that if you are caught cheating but get away with it then you don’t deserve the championship, but if you cheat in a way that is never found out until years later then you do deserve the championship for successfully outsmarting the organisers. If the launch control button was only discovered now I would say it was impressive that they kept it secret and deserved the championship, but the fact that it was known about at the time but Benetton wormed their way out of punishment means, for me, they cannot be the rightful champions of 1994.

Qeki (@qeki)

12th January 2023, 20:08

@f1frog Human mind works quite one sided. Win in any way possible. If you get caught act stupid Rules are rules and they are made to be broken e.t.c. As once one man said: “It is much easier to win by cheating than lose. But if you get caught it doesn’t matter because you have already won and lost at the same time.”

Jason (@jasonj)

13th January 2023, 1:57

A cheat is a cheat, whether it running into your competitor or knowingly driving with traction control, it’s all a cheat and very much despicable. Most cheats will justify their actions, by claiming ‘everyone else is also cheating, but we are just better at cheating than they are.’ There is no satisfaction in cheating (there is money), you know you couldn’t do it straight and fair, so that will slowly eat away at you unless you have contempt for your competition.

Flavio is and always will be a cheat at everything he does, he just doesn’t care one iota, he’s more than likely proud of it. Screwing over competitors is his most satisfying achievement it seems.

It’s sad that everyone looks at Schumacher as one of the best, yet he’s a blatant and obvious cheat, if he wasn’t incapacitated and have this built in pity, I think he would be savaged by more critical people.

Btw, I think there is a difference between technological achievements and blatant rule breaking, you can design and implement a method of gaining an advantage, but if it’s targeted to bypass scrutineering and knowingly breaking rules, it’s cheating.

Apophis (@apophisjj)

12th January 2023, 20:43

They are just a fashion label who are not bringing anything valuable to Formula 1. They just want publicity…

Unicron (@unicron2002)

12th January 2023, 22:56

Great run through of the team. A lot of good looking cars there, my favourites being the ones in the late 80s, 92, 94, 97 and 98.

bernasaurus (@bernasaurus)

13th January 2023, 0:20

I think when it comes to cars, and other such things. The ones from when you were a kid are more often than not your favourite. Stuff that comes after, just isn’t quite the same. For some here it might be Emersons’ Lotus 72, or Ayrton in an MP4/4. Heck there will be some here who remember Stirling sliding about in his Mercedes and have fond memories.

But for me, the B194 is just beautiful, I can’t look at that nose and not smile. I don’t care about legality, I just think its stunning.

When I first watched F1, Ayrton was the star, but I went for this plucky young upstart called Michael with his weird colourful greens and blues splashed all over his car. I used to spend hours drawing the blue stripe that runs off the nose back to the cockpit, swishing and thining out as it goes pretending its being affected by the air passing over the car. It made it look fast.

Even the onboards, Michael had this raised cockpit interface, you could see the revs flash across the dash and watch him change gear when it hit red. Damons FW16 looked like they’d squished him into the tiniest space, it looked cramp and you couldn’t see anything he was doing anyway.

If i’d been born ten years earlier or later, it would have been a different car. But I could look at a B194 anytime. Watching Spain 94′ as a kid, even when the car wasn’t working, and my dad explaining what ‘stuck in gear’ meant, I felt like Michael was a superhero and he’d figure it out. And he did.